Great March On Washington on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in

Noted singer Marian Anderson was scheduled to lead the National Anthem but was unable to arrive on time; Camilla Williams performed in her place. Following an invocation by Washington's Roman Catholic Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director

Noted singer Marian Anderson was scheduled to lead the National Anthem but was unable to arrive on time; Camilla Williams performed in her place. Following an invocation by Washington's Roman Catholic Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director

Lewis' speech was distributed to fellow organizers the evening before the march; Reuther, O'Boyle, and others thought it was too divisive and militant. O'Boyle objected most strenuously to a part of the speech that called for immediate action and disavowed "patience." The government and moderate organizers could not countenance Lewis's explicit opposition to Kennedy's civil rights bill. That night, O'Boyle and other members of the Catholic delegation began preparing a statement announcing their withdrawal from the March. Reuther convinced them to wait and called Rustin; Rustin informed Lewis at 2 A.M. on the day of the march that his speech was unacceptable to key coalition members. (Rustin also reportedly contacted Tom Kahn, mistakenly believing that Kahn had edited the speech and inserted the line about Sherman's March to the Sea. Rustin asked, "How could you do this? Do you know what Sherman ''did''?) But Lewis did not want to change the speech. Other members of SNCC, including Stokely Carmichael, were also adamant that the speech not be censored. The dispute continued until minutes before the speeches were scheduled to begin. Under threat of public denouncement by the religious leaders, and under pressure from the rest of his coalition, Lewis agreed to omit the 'inflammatory' passages. Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of Lewis's speech. In the end, Lewis added a qualified endorsement of Kennedy's civil rights legislation, saying: "It is true that we support the administration's Civil Rights Bill. We support it with great reservation, however." Even after toning down his speech, Lewis called for activists to "get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes".

Lewis' speech was distributed to fellow organizers the evening before the march; Reuther, O'Boyle, and others thought it was too divisive and militant. O'Boyle objected most strenuously to a part of the speech that called for immediate action and disavowed "patience." The government and moderate organizers could not countenance Lewis's explicit opposition to Kennedy's civil rights bill. That night, O'Boyle and other members of the Catholic delegation began preparing a statement announcing their withdrawal from the March. Reuther convinced them to wait and called Rustin; Rustin informed Lewis at 2 A.M. on the day of the march that his speech was unacceptable to key coalition members. (Rustin also reportedly contacted Tom Kahn, mistakenly believing that Kahn had edited the speech and inserted the line about Sherman's March to the Sea. Rustin asked, "How could you do this? Do you know what Sherman ''did''?) But Lewis did not want to change the speech. Other members of SNCC, including Stokely Carmichael, were also adamant that the speech not be censored. The dispute continued until minutes before the speeches were scheduled to begin. Under threat of public denouncement by the religious leaders, and under pressure from the rest of his coalition, Lewis agreed to omit the 'inflammatory' passages. Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of Lewis's speech. In the end, Lewis added a qualified endorsement of Kennedy's civil rights legislation, saying: "It is true that we support the administration's Civil Rights Bill. We support it with great reservation, however." Even after toning down his speech, Lewis called for activists to "get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes".

Joan Baez led the crowds in several verses of " We Shall Overcome" and " Oh Freedom". Musician Bob Dylan performed " When the Ship Comes In", for which he was joined by Baez. Dylan also performed " Only a Pawn in Their Game", a provocative and not completely popular choice because it asserted that

Joan Baez led the crowds in several verses of " We Shall Overcome" and " Oh Freedom". Musician Bob Dylan performed " When the Ship Comes In", for which he was joined by Baez. Dylan also performed " Only a Pawn in Their Game", a provocative and not completely popular choice because it asserted that

After the March, the speakers travelled to the White House for a brief discussion of proposed civil rights legislation with President Kennedy. As the leaders approached The White House, the media reported that Reuther said to King, "Everything was perfect, just perfect." Kennedy had watched King's speech on TV and was very impressed. According to biographer

After the March, the speakers travelled to the White House for a brief discussion of proposed civil rights legislation with President Kennedy. As the leaders approached The White House, the media reported that Reuther said to King, "Everything was perfect, just perfect." Kennedy had watched King's speech on TV and was very impressed. According to biographer

The Forgotten Radical History of the March on Washington

; ''Dissent'', Spring 2013. The mass media identified King's speech as a highlight of the event and focused on this oration to the exclusion of other aspects. For several decades, King took center stage in narratives about the March. More recently, historians and commentators have acknowledged the role played by Bayard Rustin in organizing the event.DeWayne Wickham,

Rustin finally getting due recognition

; ''Pacific Daily News'', 15 August 2013. The March was an early example of social movements conducting mass rallies in Washington, D.C., and was followed by several other marches in the capital, many of which used similar names. For the 50th Anniversary, of the March, the United States Postal Service released a forever stamp that commemorated it.

The 1963 March on Washington Changed Politics Forever

; ''The Fiscal Times'', 9 August 2013. The cooperation of a Democratic administration with the issue of civil rights marked a pivotal moment in voter alignment within the U.S. The Democratic Party gave up the Solid South—its undivided support since Reconstruction among the segregated Southern states—and went on to capture a high proportion of votes from black people from the Republicans.

The 1963 March also spurred anniversary marches that occur every five years, with the 20th and 25th being some of the most well known. The 20th Anniversary theme was "We Still have a Dream ... Jobs*Peace*Freedom."

At the 50th anniversary march in 2013, President Barack Obama conferred a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom on Bayard Rustin and 15 others.

The 1963 March also spurred anniversary marches that occur every five years, with the 20th and 25th being some of the most well known. The 20th Anniversary theme was "We Still have a Dream ... Jobs*Peace*Freedom."

At the 50th anniversary march in 2013, President Barack Obama conferred a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom on Bayard Rustin and 15 others.

50 Years After the March On Washington: The Economic Impacts on Education

; ''Huffington Post'', 13 August 2013.

File:Poitier Belafonte Heston Civil Rights March 1963.jpg,

March on Washington

– ''King Encyclopedia'',

March on Washington August 28, 1963

– Civil Rights Movement Archive

WDAS History

The 1963 March on Washington

– slideshow by ''

Original Program for the March on Washington

Martin Luther King Jr.'s speech at the March

March on Washington 50th Anniversary Oral History Project

District of Columbia Public Library

Color photos from 1963 March on Washington

Collection by CNN Video

John Lewis's speech

*

The March, 1963, from the National Archives YouTube Channel

* {{Authority control 1963 in Washington, D.C. 1963 protests Articles containing video clips August 1963 events in the United States Civil rights movement Civil rights protests in the United States History of African-American civil rights Martin Luther King Jr. Protest marches in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rights of African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

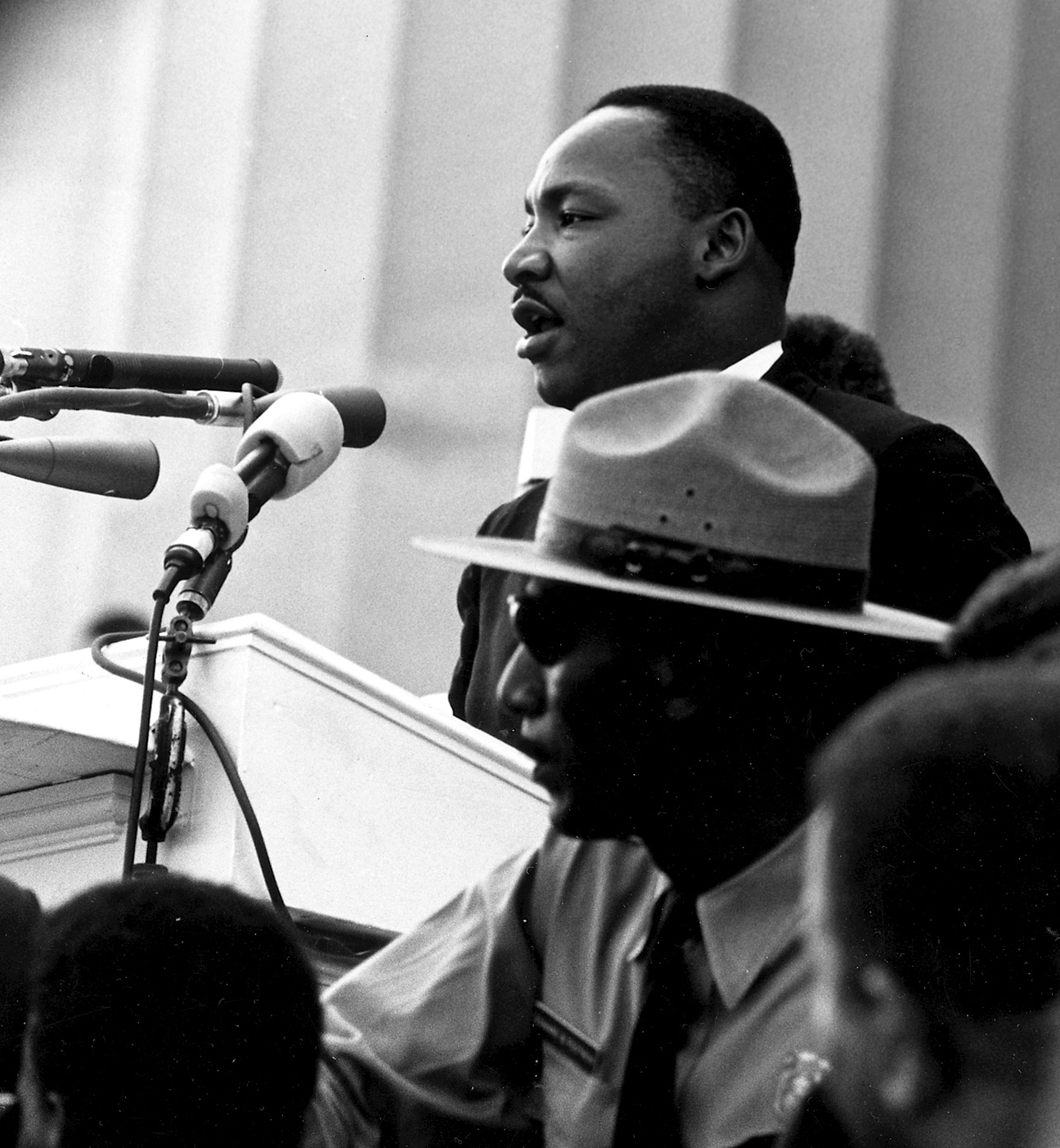

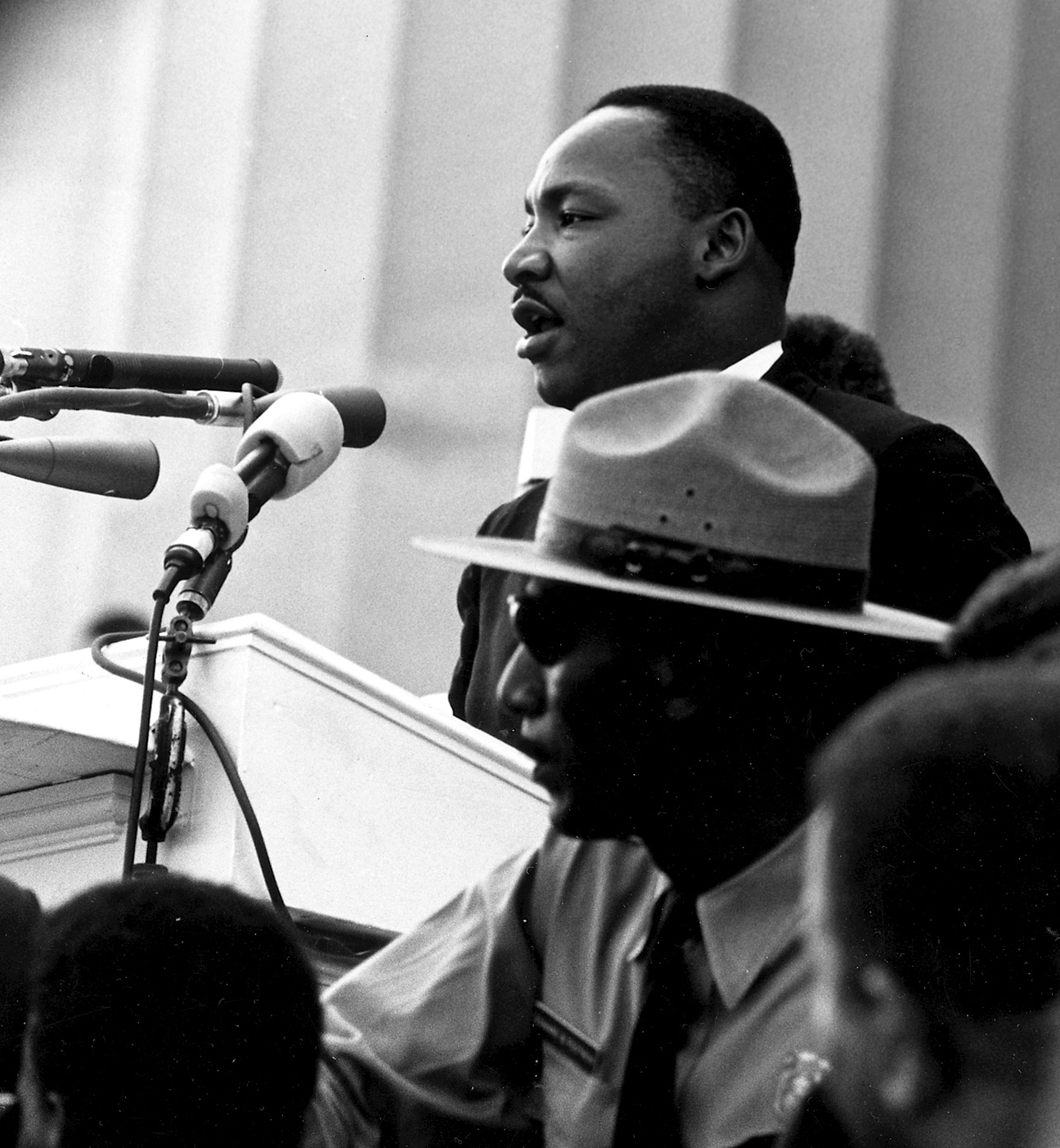

s. At the march, final speaker Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in the ...

, delivered his historic "I Have a Dream

"I Have a Dream" is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called ...

" speech in which he called for an end to racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

.

The march was organized by A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American led labor union. In ...

and Bayard Rustin, who built an alliance of civil rights, labor, and religious organizations that came together under the banner of "jobs and freedom." Estimates of the number of participants varied from 200,000 to 300,000, but the most widely cited estimate is 250,000 people. Observers estimated that 75–80% of the marchers were black. The march was one of the largest political rallies

A political demonstration is an action by a mass group or collection of groups of people in favor of a political or other cause or people partaking in a protest against a cause of concern; it often consists of walking in a mass march formati ...

for human rights in United States history. Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers

The International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, better known as the United Auto Workers (UAW), is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico ...

, was the most integral and highest-ranking white organizer of the march.

The march is credited with helping to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. It preceded the Selma Voting Rights Movement

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized ...

, when national media coverage contributed to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement ...

that same year.

Background

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

were legally freed from slavery under the Thirteenth Amendment and granted citizenship in the Fourteenth Amendment, and African American men were elevated to the status of citizens and granted full voting rights by the Fifteenth Amendment in the years soon after the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, but conservative Democrats regained power after the end of the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

(in 1877) and imposed many restrictions on people of color in the South. At the turn of the century, Southern states passed constitutions and laws that disenfranchised most black people and many poor whites, excluding them from the political system. The whites imposed social, economic, and political repression against black people into the 1960s, under a system of legal discrimination known as Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

, which were pervasive in the American South

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Black people suffered discrimination from private businesses as well, and most were prevented from voting, sometimes through violent means. Twenty-one states prohibited interracial marriage.

During the 20th century, civil rights organizers began to develop ideas for a march on Washington, DC, to seek justice. Earlier efforts to organize such a demonstration included the March on Washington Movement

The March on Washington Movement (MOWM), 1941–1946, organized by activists A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin was a tool designed to pressure the U.S. government into providing fair working opportunities for African Americans and desegregating ...

of the 1940s. A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American led labor union. In ...

—the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Founded in 1925, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The BSCP gathered a membership of 18,000 passenger railwa ...

, president of the Negro American Labor Council, and vice president of the AFL–CIO—was a key instigator in 1941. With Bayard Rustin, Randolph called for 100,000 black workers to march on Washington, in protest of discriminatory hiring during World War II by U.S. military contractors and demanding an Executive Order to correct that. Faced with a mass march scheduled for July 1, 1941, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

issued Executive Order 8802

Executive Order 8802 was signed by President of the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, to prohibit ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation's defense industry. It also set up the Fair Employment Practice Committ ...

on June 25. The order established the Committee on Fair Employment Practice

The Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) was created in 1941 in the United States to implement Executive Order 8802 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt "banning discriminatory employment practices by Federal agencies and all unions and comp ...

and banned discriminatory hiring in the defense industry, leading to improvements for many defense workers. Randolph called off the March.

Randolph and Rustin continued to organize around the idea of a mass march on Washington. They envisioned several large marches during the 1940s, but all were called off (despite criticism from Rustin). Their Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom

The Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, or Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington, was a 1957 demonstration in Washington, D.C., an early event in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. It was the occasion for Martin Luther King Jr.'s ''Give Us th ...

, held at the Lincoln Memorial on May 17, 1957, featured key leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Roy Wilkins. Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson ( ; born Mahala Jackson; October 26, 1911 – January 27, 1972) was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to t ...

performed.

The 1963 march was part of the rapidly expanding Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, which involved demonstrations and nonviolent direct action

Direct action originated as a political activism, activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic power, economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those a ...

across the United States. 1963 marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. Leaders represented major civil rights organizations. Members of The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

put aside their differences and came together for the march. Many whites and black people also came together in the urgency for change in the nation.

That year violent confrontations broke out in the South: in Cambridge, Maryland; Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Goldsboro, North Carolina; Somerville, Tennessee; Saint Augustine, Florida; and across Mississippi. In most cases, white people attacked nonviolent demonstrators seeking civil rights. Many people wanted to march on Washington, but disagreed over how the march should be conducted. Some called for a complete shutdown of the city through civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

. Others argued that the civil rights movement should remain nationwide in scope, rather than focus its energies on the nation's capital and federal government. There was a widespread perception that the Kennedy administration had not lived up to its promises in the 1960 election, and King described Kennedy's race policy as "tokenism".

On May 24, 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, a ...

invited African-American novelist James Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer. He garnered acclaim across various media, including essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', was published in 1953; de ...

, along with a large group of cultural leaders, to a meeting in New York to discuss race relations. However, the meeting became antagonistic, as black delegates felt that Kennedy did not have an adequate understanding of the race problem in the nation. The public failure of the meeting, which came to be known as the Baldwin–Kennedy meeting

The Baldwin–Kennedy meeting of May 24, 1963 was an attempt to improve race relations in the United States. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy invited novelist James Baldwin, along with a large group of cultural leaders, to meet in a Kennedy a ...

, underscored the divide between the needs of Black America and the understanding of Washington politicians. But the meeting also provoked the Kennedy administration to take action on the civil rights for African Americans. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy gave a notable civil rights address

The Report to the American People on Civil Rights was a speech on civil rights, delivered on radio and television by United States President John F. Kennedy from the Oval Office on June 11, 1963 in which he proposed legislation that would later b ...

on national television and radio, announcing that he would begin to push for civil rights legislation. After his assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

, his proposal was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson as the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. That night (early morning of June 12, 1963), Mississippi activist Medgar Evers was murdered in his own driveway, further escalating national tension around the issue of racial inequality.

Planning and organization

A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American led labor union. In ...

and Bayard Rustin began planning the march in December 1961. They envisioned two days of protest, including sit-ins and lobbying followed by a mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial. They wanted to focus on joblessness and to call for a public works program that would employ black people. In early 1963 they called publicly for "a massive March on Washington for jobs". They received help from Stanley Aronowitz

Stanley Aronowitz (January 6, 1933 – August 16, 2021) was a professor of sociology, cultural studies, and urban education at the CUNY Graduate Center. He was also a veteran political activist and cultural critic, an advocate for organized labo ...

of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers

Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) was a United States labor union known for its support for "social unionism" and progressive political causes. Led by Sidney Hillman for its first thirty years, it helped found the Congress of Ind ...

; he gathered support from radical organizers who could be trusted not to report their plans to the Kennedy administration. The unionists offered tentative support for a march that would be focused on jobs.

On May 15, 1963, without securing the cooperation of the NAACP or the Urban League, Randolph announced an "October Emancipation March on Washington for Jobs". He reached out to union leaders, winning the support of the UAW's Walter Reuther, but not of AFL–CIO president George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union leader for 57 years. He was the key figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as the AFL–CIO's first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son ...

.Euchner, ''Nobody Turn Me Around'' (2010), p. 21. Randolph and Rustin intended to focus the March on economic inequality, stating in their original plan that "integration in the fields of education, housing, transportation and public accommodations will be of limited extent and duration so long as fundamental economic inequality along racial lines persists." As they negotiated with other leaders, they expanded their stated objectives to "Jobs and Freedom", to acknowledge the agenda of groups that focused more on civil rights.

In June 1963, leaders from several different organizations formed the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership, an umbrella group to coordinate funds and messaging. This coalition of leaders, who became known as the " Big Six", included: Randolph, chosen as titular head of the march; James Farmer, president of the Congress of Racial Equality; John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

; Roy Wilkins, president of the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

; and Whitney Young

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an American civil rights leader. Trained as a social worker, he spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban ...

, president of the National Urban League. King in particular had become well known for his role in the Birmingham campaign and for his Letter from Birmingham Jail

The "Letter from Birmingham Jail", also known as the "Letter from Birmingham City Jail" and "The Negro Is Your Brother", is an open letter written on April 16, 1963, by Martin Luther King Jr. It says that people have a moral responsibility to b ...

. Wilkins and Young initially objected to Rustin as a leader for the march, worried that he would attract the wrong attention because he was a homosexual, a former Communist, and a draft resister. They eventually accepted Rustin as deputy organizer, on the condition that Randolph act as lead organizer and manage any political fallout.

About two months before the march, the Big Six broadened their organizing coalition by bringing on board four white men who supported their efforts: Walter Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers; Eugene Carson Blake

Eugene Carson Blake (November 7, 1906 – July 31, 1985) was an American Presbyterian Church leader.

From 1954 to 1957 he served as president of the National Council of Churches in the United States; from 1966 to 1972 he served as General Sec ...

, former president of the National Council of Churches; Mathew Ahmann

Mathew H. Ahmann (September 10, 1931 – December 31, 2001) was an American Catholic layman and civil rights activist. He was a leader of the Catholic Church's involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and in 1960 founded and became the executi ...

, executive director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice; and Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress

The American Jewish Congress (AJCongress or AJC) is an association of American Jews organized to defend Jewish interests at home and abroad through public policy advocacy, using diplomacy, legislation, and the courts.

History

The AJCongress was ...

. Together, the Big Six plus four became known as the "Big Ten." John Lewis later recalled, "Somehow, some way, we worked well together. The six of us, plus the four. We became like brothers."

On June 22, the organizers met with President Kennedy, who warned against creating "an atmosphere of intimidation" by bringing a large crowd to Washington. The civil rights activists insisted on holding the march. Wilkins pushed for the organizers to rule out civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

and described this proposal as the "perfect compromise". King and Young agreed. Leaders from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

(SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who wanted to conduct direct actions against the Department of Justice, endorsed the protest before they were informed that civil disobedience would not be allowed. Finalized plans for the March were announced in a press conference on July 2. President Kennedy spoke favorably of the March on July 17, saying that organizers planned a peaceful assembly and had cooperated with the Washington, D.C., police.

Mobilization and logistics were administered by Rustin, a civil rights veteran and organizer of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first of the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions '' Morgan v. Virginia ...

to test the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

ruling that banned racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

in interstate travel. Rustin was a long-time associate of both Randolph and Dr. King. With Randolph concentrating on building the march's political coalition, Rustin built and led the team of two hundred activists and organizers who publicized the march and recruited the marchers, coordinated the buses and trains, provided the marshals, and set up and administered all of the logistic details of a mass march in the nation's capital. During the days leading up to the march, these 200 volunteers used the ballroom of Washington DC radio station WUST as their operations headquarters.

The march was not universally supported among civil rights activists. Some, including Rustin (who assembled 4,000 volunteer marshals from New York), were concerned that it might turn violent, which could undermine pending legislation and damage the international image of the movement. The march was condemned by Malcolm X, spokesperson for the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

, who termed it the "farce on Washington".

March organizers disagreed about the purpose of the march. The NAACP and Urban League saw it as a gesture of support for the civil rights bill that had been introduced by the Kennedy

Kennedy may refer to:

People

* John F. Kennedy (1917–1963), 35th president of the United States

* John Kennedy (Louisiana politician), (born 1951), US Senator from Louisiana

* Kennedy (surname), a family name (including a list of persons with t ...

Administration. Randolph, King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civi ...

(SCLC) believed it could raise both civil rights and economic issues to national attention beyond the Kennedy bill. CORE and SNCC believed the march could challenge and condemn the Kennedy administration's inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans.

Despite their disagreements, the group came together on a set of goals:

* Passage of meaningful civil rights legislation;

* Immediate elimination of school segregation (the Supreme Court had ruled that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional in 1954, in '' Brown v. Board of Education'');

* A program of public works, including job training, for the unemployed;

* A Federal law prohibiting discrimination in public or private hiring;

* A $2-an-hour minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Bec ...

nationwide ();

* Withholding Federal funds from programs that tolerate discrimination;

* Enforcement of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution by reducing congressional representation from States that disenfranchise citizens;

* A Fair Labor Standards Act broadened to include employment areas then excluded;

* Authority for the Attorney General to institute injunctive suits when constitutional rights of citizens are violated.

Although in years past, Randolph had supported "Negro only" marches, partly to reduce the impression that the civil rights movement was dominated by white communists, organizers in 1963 agreed that white and black people marching side by side would create a more powerful image.

The Kennedy Administration cooperated with the organizers in planning the March, and one member of the Justice Department was assigned as a full-time liaison.Barber, ''Marching on Washington'' (2002), p. 151. Chicago and New York City (as well as some corporations) agreed to designate August 28 as "Freedom Day" and give workers the day off.

To avoid being perceived as radical, organizers rejected support from Communist groups. However, some politicians claimed that the March was Communist-inspired, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI) produced numerous reports suggesting the same. In the days before August 28, the FBI called celebrity backers to inform them of the organizers' communist connections and advising them to withdraw their support. When William C. Sullivan

William Cornelius Sullivan (May 12, 1912 – November 9, 1977) was a Federal Bureau of Investigation official who directed the agency's domestic intelligence operations from 1961 to 1971. Sullivan was forced out of the FBI at the end of Septembe ...

produced a lengthy report on August 23 suggesting that Communists had failed to appreciably infiltrate the civil rights movement, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

rejected its contents. Strom Thurmond

James Strom Thurmond Sr. (December 5, 1902June 26, 2003) was an American politician who represented South Carolina in the United States Senate from 1954 to 2003. Prior to his 48 years as a senator, he served as the 103rd governor of South Caro ...

launched a prominent public attack on the March as Communist, and singled out Rustin in particular as a Communist and a gay man.

Organizers worked out of a building at West 130th St. and Lenox in Harlem. They promoted the march by selling buttons, featuring two hands shaking, the words "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom", a union bug, and the date August 28, 1963. By August 2, they had distributed 42,000 of the buttons. Their goal was a crowd of at least 100,000 people.Barber, ''Marching on Washington'' (2002), p. 156.

As the march was being planned, activists across the country received bomb threats at their homes and in their offices. The ''Los Angeles Times'' received a message saying its headquarters would be bombed unless it printed a message calling the president a "Nigger Lover". Five airplanes were grounded on the morning of August 28 due to bomb threats. A man in Kansas City telephoned the FBI to say he would put a hole between King's eyes; the FBI did not respond. Roy Wilkins was threatened with assassination if he did not leave the country.

Convergence

Thousands traveled by road, rail, and air to Washington, D.C., on Wednesday, August 28. Marchers from Boston traveled overnight and arrived in Washington at 7am after an eight-hour trip, but others took much longer bus rides from cities such as Milwaukee, Little Rock, and St. Louis. Organizers persuaded New York's MTA to run extra subway trains after midnight on August 28, and the New York City bus terminal was busy throughout the night with peak crowds. A total of 450 buses left New York City from Harlem. Maryland police reported that "by 8:00 a.m., 100 buses an hour were streaming through the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel." The United Automobile Workers financed bus transportation for 5,000 of its rank-and-file members, providing the largest single contingent from any organization. One reporter, Fred Powledge, accompanied African Americans who boarded six buses in Birmingham, Alabama, for the 750-mile trip to Washington. The '' New York Times'' carried his report:The 260 demonstrators, of all ages, carried picnic baskets, water jugs, Bibles and a major weapon—their willingness to march, sing and pray in protest against discrimination. They gathered early this morning ugust 27in Birmingham'sJohn Marshall Kilimanjaro, a demonstrator traveling from Greensboro, North Carolina, said:Kelly Ingram Park Kelly Ingram Park, formerly West Park, is a park located in Birmingham, Alabama. It is bounded by 16th and 17th Streets and 5th and 6th Avenues North in the Birmingham Civil Rights District. The park, just outside the doors of the 16th Street Ba ..., where state troopers onceour months previous in May Our or OUR may refer to: * The possessive form of "we" * Our (river), in Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany * Our, Belgium, a village in Belgium * Our, Jura, a commune in France * Office of Utilities Regulation (OUR), a Politics of Jamaica#Regulator ...used fire hoses and dogs to put down their demonstrations. It was peaceful in the Birmingham park as the marchers waited for the buses. The police, now part of a moderate city power structure, directed traffic around the square and did not interfere with the gathering ... An old man commented on the 20-hour ride, which was bound to be less than comfortable: "You forget we Negroes have been riding buses all our lives. We don't have the money to fly in airplanes."

Contrary to the mythology, the early moments of the March—getting there—was no picnic. People were afraid. We didn't know what we would meet. There was no precedent. Sitting across from me was a black preacher with a white collar. He was an AME preacher. We talked. Every now and then, people on the bus sang 'Oh Freedom' and 'We Shall Overcome,' but for the most part there wasn't a whole bunch of singing. We were secretly praying that nothing violent happened.Other bus rides featured racial tension, as black activists criticized liberal white participants as fair-weather friends. Hazel Mangle Rivers, who had paid $8 for her ticket—"one-tenth of her husband's weekly salary"—was quoted in the August 29 ''New York Times''. Rivers said that she was impressed by Washington's civility:

The people are lots better up here than they are down South. They treat you much nicer. Why, when I was out there at the march a white man stepped on my foot, and he said, "Excuse me," and I said "Certainly!" That's the first time that has ever happened to me. I believe that was the first time a white person has ever really been nice to me.Some participants who arrived early held an all-night vigil outside the Department of Justice, claiming it had unfairly targeted civil rights activists and that it had been too lenient on white supremacists who attacked them.

Security preparations

The Washington, D.C., police forces were mobilized to full capacity for the march, including reserve officers and deputized firefighters. A total of 5,900 police officers were on duty. The government mustered 2,000 men from the National Guard, and brought in 3,000 outside soldiers to join the 1,000 already stationed in the area. These additional soldiers were flown in on helicopters from bases in Virginia and North Carolina. The Pentagon readied 19,000 troops in the suburbs. All of the forces involved were prepared to implement a coordinated conflict strategy named "Operation Steep Hill". For the first time since Prohibition, liquor sales were banned in Washington D.C. Hospitals stockpiled blood plasma and cancelled elective surgeries. Major League Baseball cancelled two games between the Minnesota Twins and the last place Washington Senators although the venue, D.C. Stadium, was nearly four miles from the Lincoln Memorial rally site. Rustin and Walter Fauntroy negotiated some security issues with the government, gaining approval for private marshals with the understanding that these would not be able to act against outside agitators. The FBI and Justice Department refused to provide preventive guards for buses traveling through the South to reach D.C. William Johnson recruited more than 1,000 police officers to serve on this private force.Julius Hobson

Julius Wilson Hobson (May 29, 1922March 23, 1977) was an activist and politician who served on the Council of the District of Columbia and the District of Columbia Board of Education.

Early life

Hobson was a native of Birmingham, Alabama, He wa ...

, an FBI informant who served on the March's security force, told the team to be on the lookout for FBI infiltrators who might act as agents provocateurs. Jerry Bruno, President Kennedy's advance man, was positioned to cut the power to the public address system in the event of any incendiary rally speech.

Venue and sound system

The organizers originally planned to hold the march outside the Capitol Building. However, Reuther persuaded them to move the march to theLincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in the ...

. He believed the Lincoln Memorial would be less threatening to Congress and the occasion would be appropriate underneath the gaze of President Abraham Lincoln's statue. The committee, notably Rustin, agreed to move the site on the condition that Reuther pay for a $19,000 (equivalent to $172,500 in 2021) sound system so that everyone on the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institut ...

could hear the speakers and musicians.

Rustin pushed hard for the expensive sound system, maintaining that "We cannot maintain order where people cannot hear." The system was obtained and set up at the Lincoln Memorial, but was sabotaged on the day before the March. Its operators were unable to repair it. Fauntroy contacted Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, a ...

and his civil rights liaison Burke Marshall, demanding that the government fix the system. Fauntroy reportedly told them: "We have a couple hundred thousand people coming. Do you want a fight here tomorrow after all we've done?" The system was successfully rebuilt overnight by the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

March

The march commanded national attention by preempting regularly scheduled television programs. As the first ceremony of such magnitude ever initiated and dominated by African Americans, the march also was the first to have its nature wholly misperceived in advance. Dominant expectations ran from paternal apprehension to dread. On '' Meet the Press'', reporters grilled Roy Wilkins and Martin Luther King Jr. about widespread foreboding that "it would be impossible to bring more than 100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incidents and possibly rioting." ''Life'' magazine declared that the capital was suffering "its worst case of invasion jitters since the First Battle of Bull Run." The jails shifted inmates to other prisons to make room for those arrested in mass arrest. With nearly 1,700 extra correspondents supplementing the Washington press corps, the march drew a media assembly larger than the Kennedy inauguration two years earlier. Students from the University of California, Berkeley came together as black power organizations and emphasized the importance of the African-American freedom struggle. The march included black political parties; and William Worthy was one of many who led college students during the freedom struggle era. On August 28, more than 2,000bus

A bus (contracted from omnibus, with variants multibus, motorbus, autobus, etc.) is a road vehicle that carries significantly more passengers than an average car or van. It is most commonly used in public transport, but is also in use for cha ...

es, 21 chartered trains, 10 chartered airliners, and uncounted cars converged on Washington. All regularly scheduled planes, trains, and buses were also filled to capacity.

Although Randolph and Rustin had originally planned to fill the streets of Washington, D.C., the final route of the March covered only half of the National Mall. The march began at the Washington Monument and was scheduled to progress to the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in the ...

. Demonstrators were met at the monument by the speakers and musicians. Women leaders were asked to march down Independence Avenue, while the male leaders marched on Pennsylvania Avenue with the media.

The start of the March was delayed because its leaders were meeting with members of Congress. To the leaders' surprise, the assembled group began to march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.S. national memorial built to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., across from the Washington Monument, and is in the ...

without them. The leaders met the March at Constitution Avenue, where they linked arms at the head of a crowd in order to be photographed 'leading the march'.

Marchers were not supposed to create their own signs, though this rule was not completely enforced by marshals. Most of the demonstrators did carry pre-made signs, available in piles at the Washington Monument. The UAW provided thousands of signs that, among other things, read: "There Is No Halfway House on the Road to Freedom," "Equal Rights and Jobs NOW," "UAW Supports Freedom March," "in Freedom we are Born, in Freedom we must Live," and "Before we'll be a Slave, we'll be Buried in our Grave."

About 50 members of the American Nazi Party staged a counter-protest and were quickly dispersed by police. The rest of Washington was quiet during the March. Most non-participating workers stayed home. Jailers allowed inmates to watch the March on TV.

Speakers

Representatives from each of the sponsoring organizations addressed the crowd from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial. Speakers (dubbed "The Big Ten") included The Big Six; three religious leaders (Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish); and labor leader Walter Reuther. None of the official speeches was by a woman. Dancer and actress Josephine Baker gave a speech during the preliminary offerings, but women were limited in the official program to a "tribute" led by Bayard Rustin, at which Daisy Bates also spoke briefly (see "excluded speakers" below.)Floyd McKissick

Floyd Bixler McKissick (March 9, 1922 – April 28, 1991) was an American lawyer and civil rights activist. He became the first African-American student at the University of North Carolina School of Law. In 1966 he became leader of CORE, the Congr ...

read James Farmer's speech because Farmer had been arrested during a protest in Louisiana; Farmer wrote that the protests would not stop "until the dogs stop biting us in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

and the rats stop biting us in the North."

The order of the speakers was as follows:

*1. A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American led labor union. In ...

– March Director

*2. Walter Reuther – UAW, AFL–CIO

*3. Roy Wilkins – NAACP

*4. John Lewis – Chair, SNCC

*5. Daisy Bates – Little Rock, Arkansas

*6. Dr. Eugene Carson Blake

Eugene Carson Blake (November 7, 1906 – July 31, 1985) was an American Presbyterian Church leader.

From 1954 to 1957 he served as president of the National Council of Churches in the United States; from 1966 to 1972 he served as General Sec ...

– United Presbyterian Church and the National Council of Churches

*7. Floyd McKissick

Floyd Bixler McKissick (March 9, 1922 – April 28, 1991) was an American lawyer and civil rights activist. He became the first African-American student at the University of North Carolina School of Law. In 1966 he became leader of CORE, the Congr ...

– CORE

*8. Whitney Young

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an American civil rights leader. Trained as a social worker, he spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban ...

– National Urban League

*9. Several smaller speeches were made, including by Rabbi Joachim Prinz – American Jewish Congress, Mathew Ahmann

Mathew H. Ahmann (September 10, 1931 – December 31, 2001) was an American Catholic layman and civil rights activist. He was a leader of the Catholic Church's involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and in 1960 founded and became the executi ...

– National Catholic Conference, and Josephine Baker – dancer and actress

*10. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – SCLC. His "I Have a Dream" speech has become celebrated for its vision and eloquence.

Closing remarks were made by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, March Organizers, leading with The Pledge and a list of demands.

Official program

Noted singer Marian Anderson was scheduled to lead the National Anthem but was unable to arrive on time; Camilla Williams performed in her place. Following an invocation by Washington's Roman Catholic Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director

Noted singer Marian Anderson was scheduled to lead the National Anthem but was unable to arrive on time; Camilla Williams performed in her place. Following an invocation by Washington's Roman Catholic Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, the opening remarks were given by march director A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph (April 15, 1889 – May 16, 1979) was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American led labor union. In ...

, followed by Eugene Carson Blake

Eugene Carson Blake (November 7, 1906 – July 31, 1985) was an American Presbyterian Church leader.

From 1954 to 1957 he served as president of the National Council of Churches in the United States; from 1966 to 1972 he served as General Sec ...

.

A tribute to "Negro Women Fighters for Freedom" was led by Bayard Rustin, at which Daisy Bates spoke briefly in place of Myrlie Evers, who had missed her flight. The tribute introduced Daisy Bates, Diane Nash, Prince E. Lee

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

, Rosa Parks, and Gloria Richardson.

Following that, speakers were SNCC chairman John Lewis, labor leader Walter Reuther, and CORE chairman Floyd McKissick

Floyd Bixler McKissick (March 9, 1922 – April 28, 1991) was an American lawyer and civil rights activist. He became the first African-American student at the University of North Carolina School of Law. In 1966 he became leader of CORE, the Congr ...

(substituting for arrested CORE director James Farmer). The Eva Jessye Choir sang, and Rabbi Uri Miller (president of the Synagogue Council of America) offered a prayer. He was followed by National Urban League director Whitney Young

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an American civil rights leader. Trained as a social worker, he spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban ...

, NCCIJ director Mathew Ahmann

Mathew H. Ahmann (September 10, 1931 – December 31, 2001) was an American Catholic layman and civil rights activist. He was a leader of the Catholic Church's involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, and in 1960 founded and became the executi ...

, and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins. After a performance by singer Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson ( ; born Mahala Jackson; October 26, 1911 – January 27, 1972) was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to t ...

, American Jewish Congress president Joachim Prinz spoke, followed by SCLC president Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Rustin read the March's official demands for the crowd's approval, and Randolph led the crowd in a pledge to continue working for the March's goals. The program was closed with a benediction by Morehouse College president Benjamin Mays.

Although one of the officially stated purposes of the march was to support the civil rights bill introduced by the Kennedy Administration, several of the speakers criticized the proposed law as insufficient. Two government agents stood by in a position to cut power to the microphone if necessary.

Roy Wilkins

Roy Wilkins announced that sociologist and activistW. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

had died in Ghana the previous night, where he had been living in exile; the crowd observed a moment of silence in his memory. Wilkins had initially refused to announce the news because he despised Du Bois for becoming a Communist—but insisted on making the announcement when he realized that Randolph would make it if he didn't. Wilkins said: "Regardless of the fact that in his later years Dr. Du Bois chose another path, it is incontrovertible that at the dawn of the twentieth century his was the voice that was calling you to gather here today in this cause. If you want to read something that applies to 1963 go back and get a volume of '' The Souls of Black Folk'' by Du Bois, published in 1903."

John Lewis

John Lewis of SNCC was the youngest speaker at the event. He planned to criticize the Kennedy Administration for the inadequacies of the Civil Rights Act of 1963. Other leaders insisted that the speech be changed to be less antagonistic to the government. James Forman and other SNCC activists contributed to the revision. It still complained that the Administration had not done enough to protect southern black people and civil rights workers from physical violence by whites in the Deep South. Deleted from his original speech at the insistence of more conservative and pro-Kennedy leaders were phrases such as: Lewis' speech was distributed to fellow organizers the evening before the march; Reuther, O'Boyle, and others thought it was too divisive and militant. O'Boyle objected most strenuously to a part of the speech that called for immediate action and disavowed "patience." The government and moderate organizers could not countenance Lewis's explicit opposition to Kennedy's civil rights bill. That night, O'Boyle and other members of the Catholic delegation began preparing a statement announcing their withdrawal from the March. Reuther convinced them to wait and called Rustin; Rustin informed Lewis at 2 A.M. on the day of the march that his speech was unacceptable to key coalition members. (Rustin also reportedly contacted Tom Kahn, mistakenly believing that Kahn had edited the speech and inserted the line about Sherman's March to the Sea. Rustin asked, "How could you do this? Do you know what Sherman ''did''?) But Lewis did not want to change the speech. Other members of SNCC, including Stokely Carmichael, were also adamant that the speech not be censored. The dispute continued until minutes before the speeches were scheduled to begin. Under threat of public denouncement by the religious leaders, and under pressure from the rest of his coalition, Lewis agreed to omit the 'inflammatory' passages. Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of Lewis's speech. In the end, Lewis added a qualified endorsement of Kennedy's civil rights legislation, saying: "It is true that we support the administration's Civil Rights Bill. We support it with great reservation, however." Even after toning down his speech, Lewis called for activists to "get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes".

Lewis' speech was distributed to fellow organizers the evening before the march; Reuther, O'Boyle, and others thought it was too divisive and militant. O'Boyle objected most strenuously to a part of the speech that called for immediate action and disavowed "patience." The government and moderate organizers could not countenance Lewis's explicit opposition to Kennedy's civil rights bill. That night, O'Boyle and other members of the Catholic delegation began preparing a statement announcing their withdrawal from the March. Reuther convinced them to wait and called Rustin; Rustin informed Lewis at 2 A.M. on the day of the march that his speech was unacceptable to key coalition members. (Rustin also reportedly contacted Tom Kahn, mistakenly believing that Kahn had edited the speech and inserted the line about Sherman's March to the Sea. Rustin asked, "How could you do this? Do you know what Sherman ''did''?) But Lewis did not want to change the speech. Other members of SNCC, including Stokely Carmichael, were also adamant that the speech not be censored. The dispute continued until minutes before the speeches were scheduled to begin. Under threat of public denouncement by the religious leaders, and under pressure from the rest of his coalition, Lewis agreed to omit the 'inflammatory' passages. Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of Lewis's speech. In the end, Lewis added a qualified endorsement of Kennedy's civil rights legislation, saying: "It is true that we support the administration's Civil Rights Bill. We support it with great reservation, however." Even after toning down his speech, Lewis called for activists to "get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes".

Martin Luther King Jr.

The speech given by SCLC president King, who spoke last, became known as the "I Have a Dream

"I Have a Dream" is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister, Martin Luther King Jr., during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, King called ...

" speech, which was carried live by TV stations and subsequently considered the most impressive moment of the march. In it, King called for an end to racism in the United States. It invoked the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

, and the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

. At the end of the speech, Mahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson ( ; born Mahala Jackson; October 26, 1911 – January 27, 1972) was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to t ...

shouted from the crowd, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!", and King departed from his prepared text for a partly improvised peroration

Dispositio is the system used for the organization of arguments in the context of Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "organization" or "arrangement".

It is the second of five canons of classical rhetoric (the ...

on the theme of "I have a dream". Over time it has been hailed as a masterpiece of rhetoric, added to the National Recording Registry and memorialized by the National Park Service with an inscription on the spot where King stood to deliver the speech.

Randolph and Rustin

A. Philip Randolph spoke first, promising: "we shall return again and again to Washington in ever growing numbers until total freedom is ours." Randolph also closed the event along with Bayard Rustin. Rustin followed King's speech by slowly reading the list of demands. The two concluded by urging attendees to take various actions in support of the struggle.Walter Reuther

Walter Reuther urged Americans to pressure their politicians to act to address racial injustices. He said,American democracy is on trial in the eyes of the world ... We cannot successfully preach democracy in the world unless we first practice democracy at home. American democracy will lack the moral credentials and be both unequal to and unworthy of leading the forces of freedom against the forces of tyranny unless we take bold, affirmative, adequate steps to bridge the moral gap between American democracy's noble promises and its ugly practices in the field of civil rights.According to

Irving Bluestone

Irving Julius Bluestone (January 5, 1917 – November 17, 2007) was an American trade union leader. He was the chief negotiator for almost a half a million workers at General Motors in the 1970s, and an advocate of worker participation in manage ...

, who was standing near the platform while Reuther delivered his remarks, he overheard two black women talking. One asked, "Who is that white man?" The other replied, "Don't you know him? That's the white Martin Luther King."

Excluded speakers

AuthorJames Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer. He garnered acclaim across various media, including essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', was published in 1953; de ...

was prevented from speaking at the March on the grounds that his comments would be too inflammatory. Baldwin later commented on the irony of the "terrifying and profound" requests that he prevent the March from happening:

In my view, by that time, there was, on the one hand, nothing to prevent—the March had already been co-opted—and, on the other, no way of stopping the people from descending on Washington. What struck me most horribly was that virtually no one in power (including some blacks or Negroes who were somewhere next door to power) was able, even remotely, to accept the depth, the dimension, of the passion and the faith of the people.Despite the protests of organizer Anna Arnold Hedgeman, no women gave a speech at the March. Male organizers attributed this omission to the "difficulty of finding a single woman to speak without causing serious problems vis-à-vis other women and women's groups". Hedgeman read a statement at an August 16 meeting, charging:

In light of the role of Negro women in the struggle for freedom and especially in light of the extra burden they have carried because of the castration of our Negro men in this culture, it is incredible that no woman should appear as a speaker at the historic March on Washington Meeting at the Lincoln Memorial.The assembled group agreed that Myrlie Evers, the new widow of Medgar Evers, could speak during the "Tribute to Women". However, Evers was unavailable, having missed her flight, and Daisy Bates spoke briefly (less than 200 words) in place of her. Earlier, Josephine Baker had addressed the crowd before the official program began. Although Gloria Richardson was on the program and had been asked to give a two-minute speech, when she arrived at the stage her chair with her name on it had been removed, and the event marshal took her microphone away after she said "hello". Richardson, along with Rosa Parks and

Lena Horne

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was an American dancer, actress, singer, and civil rights activist. Horne's career spanned more than seventy years, appearing in film, television, and theatre. Horne joined the chorus of th ...

, was escorted away from the podium before Martin Luther King Jr. spoke.

Early plans for the March would have included an "Unemployed Worker" as one of the speakers. This position was eliminated, furthering criticism of the March's middle-class bias.

Singers

Gospel legendMahalia Jackson

Mahalia Jackson ( ; born Mahala Jackson; October 26, 1911 – January 27, 1972) was an American gospel singer, widely considered one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century. With a career spanning 40 years, Jackson was integral to t ...

sang, "I've been 'buked, and I've been scorned", and " How I Got Over". Marian Anderson sang " He's Got the Whole World in His Hands". This was not Marian Anderson's first appearance at the Lincoln Memorial. In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promote ...

refused permission for Anderson to sing to an integrated audience in Constitution Hall. With the aid of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and her husband Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, Anderson performed a critically acclaimed open-air concert on Easter Sunday, 1939, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Joan Baez led the crowds in several verses of " We Shall Overcome" and " Oh Freedom". Musician Bob Dylan performed " When the Ship Comes In", for which he was joined by Baez. Dylan also performed " Only a Pawn in Their Game", a provocative and not completely popular choice because it asserted that

Joan Baez led the crowds in several verses of " We Shall Overcome" and " Oh Freedom". Musician Bob Dylan performed " When the Ship Comes In", for which he was joined by Baez. Dylan also performed " Only a Pawn in Their Game", a provocative and not completely popular choice because it asserted that Byron De La Beckwith

Byron De La Beckwith Jr. (November 9, 1920 – January 21, 2001) was an American murderer, white supremacist and member of the Ku Klux Klan from Greenwood, Mississippi. He murdered the civil rights leader Medgar Evers on June 12, 1963. Two trial ...

, as a poor white man, was not personally or primarily to blame for the murder of Medgar Evers.

Peter, Paul and Mary sang " If I Had a Hammer" and Dylan's " Blowin' in the Wind". Odetta sang " I'm On My Way".

Some participants, including Dick Gregory criticized the choice of mostly white performers and the lack of group participation in the singing. Dylan himself said he felt uncomfortable as a white man serving as a public image for the Civil Rights Movement. After the March on Washington, he performed at few other immediately politicized events.

Celebrities

The event featured many prominent celebrities in addition to singers on the program. Josephine Baker, Harry Belafonte,Sidney Poitier

Sidney Poitier ( ; February 20, 1927 – January 6, 2022) was an American actor, film director, and diplomat. In 1964, he was the first black actor and first Bahamian to win the Academy Award for Best Actor. He received two competitive ...

, James Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer. He garnered acclaim across various media, including essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', was published in 1953; de ...

, Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the baseball color line ...

, Sammy Davis, Jr.

Samuel George Davis Jr. (December 8, 1925 – May 16, 1990) was an American singer, dancer, actor, comedian, film producer and television director.

At age three, Davis began his career in vaudeville with his father Sammy Davis Sr. and the ...

, Dick Gregory, Eartha Kitt

Eartha Kitt (born Eartha Mae Keith; January 17, 1927 – December 25, 2008) was an American singer and actress known for her highly distinctive singing style and her 1953 recordings of "C'est si bon" and the Christmas novelty song "Santa Ba ...

, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee

Ruby Dee (October 27, 1922 – June 11, 2014) was an American actress, poet, playwright, screenwriter, journalist, and civil rights activist. She originated the role of "Ruth Younger" in the stage and film versions of ''A Raisin in the Sun'' (19 ...

, Diahann Carroll

Diahann Carroll (; born Carol Diann Johnson; July 17, 1935 – October 4, 2019) was an American actress, singer, model, and activist. She rose to prominence in some of the earliest major studio films to feature black casts, including ''Car ...

, and Lena Horne

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was an American dancer, actress, singer, and civil rights activist. Horne's career spanned more than seventy years, appearing in film, television, and theatre. Horne joined the chorus of th ...

were among the black celebrities attending. There were also quite a few white and Latino celebrities who attended or helped fund the March in support of the cause: Tony Curtis, James Garner, Robert Ryan, Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter; October 4, 1923April 5, 2008) was an American actor and political activist.

As a Hollywood star, he appeared in almost 100 films over the course of 60 years. He played Moses in the epic film ''The Ten C ...

, Paul Newman

Paul Leonard Newman (January 26, 1925 – September 26, 2008) was an American actor, film director, race car driver, philanthropist, and entrepreneur. He was the recipient of numerous awards, including an Academy Award, a BAFTA Award, three ...

, Joanne Woodward, Rita Moreno

Rita Moreno (born Rosa Dolores Alverío Marcano; December 11, 1931) is a Puerto Rican actress, dancer, and singer. Noted for her work across different areas of the entertainment industry, she has appeared in numerous film, television, and thea ...

, Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Considered one of the most influential actors of the 20th century, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, which spanned six decades, including two Academ ...

, Bobby Darin and Burt Lancaster

Burton Stephen Lancaster (November 2, 1913 – October 20, 1994) was an American actor and producer. Initially known for playing tough guys with a tender heart, he went on to achieve success with more complex and challenging roles over a 45-yea ...

, among others. Judy Garland was part of the planning committee and was also scheduled to perform but had to drop out at the last minute due to commitments to her TV variety series.

Meeting with President Kennedy

Thomas C. Reeves

Thomas C. Reeves (born 1936) is a U.S historian who specializes in late 19th and 20th century America.

Born into a blue collar family in Tacoma, Washington, Reeves received his B.A. at Pacific Lutheran University, his M.A. at the University of Was ...

, Kennedy "felt that he would be booed at the March, and also didn't want to meet with organizers before the March because he didn't want a list of demands. He arranged a 5 p.m. meeting at the White House with the 10 leaders on the 28th."

During the meeting, Reuther described to Kennedy how he was framing the civil rights issue to business leaders in Detroit, saying, "Look, you can't escape the problem. And there are two ways of resolving it; either by reason or riots." Reuther continued, "Now the civil war that this is gonna trigger is not gonna be fought at Gettysburg. It's gonna to be fought in your backyard, in your plant, where your kids are growing up." The March was considered a "triumph of managed protest" and Kennedy felt it was a victory for him as well—bolstering the chances for his civil rights bill.

Media coverage